Anthropomorphism on Trial

Agents are semi-autonomous software entities that perform tasks on behalf of their users. One of the attributes an agent may possess is anthropomorphism—the projection of human characteristics onto non-human or inanimate objects. As anthropomorphic agents become more common we need to consider what impact they will have on their human users. I put forward a for and against argument drawn from the current literature on anthropomorphism and then look to the future of anthropomorphic agents.

1. Introduction

As anthropomorphic agents become more common, we need to consider what impact the anthropomorphic computer will have on their human users. This article puts anthropomorphism on trial taking both for and against viewpoints. The next two sections provide a definition of agents and anthropomorphism and section four discusses anthropomorphism in three agent-based systems. Sections five and six present the relative advantages and disadvantages of anthropomorphic interfaces. Section seven discusses the implications of anthropomorphic interfaces for HCI and section eight looks to the future of anthropomorphic agents.

2. What is an Agent?

There are many definitions and ideas about what exactly an interface agent is. I will start with a simple definition of ordinary, non-computer, agents, taken from the Collins Concise English Dictionary:

agent n. 1. a person who acts on behalf of another person, business, government, etc. 2. a person or thing that acts or has the power to act. 3. a substance or organism that exerts some force or effect: a chemical agent. 4. the means by which something occurs or is achieved. 5. a person representing a business concern, esp. a travelling salesman.

The term agent is used for those in the real world (e.g. an estate agent) whereas interface agents are those used in computer interfaces. These terms are used interchangeably in the literature. “An agent is quite simply one who acts on behalf of another person. Interface agents, then, are computational entities who are capable of taking action on behalf of users” (Laurel 1989). Laurel (1991) defines agents slightly differently: “[agents are] computational characters that assist and interact with people.” According to Oren et al. (1990), “agents are, or should appear to be, autonomous software entities that make choices and execute actions on behalf of the user.” We use real or computational agents because we are unwilling or unable to perform tasks ourselves. Interface agents are appropriate for tasks requiring expertise, skill, resources, and labour—the same requirements as those for which we use real agents, e.g. estate or insurance agents.

Agents are not a separate layer between the user and the interface; they are part of the interface; Kay (1990) refers to them as “intelligent background processes.” Agents can co-operate and be combined with other agents to produce multi-agent systems (Bird 1993).

Criteria for Agents

Laurel (1990) and Foner (1993) describe their criteria for agents. Beale & Wood (1993) describe a set of attributes that make a task “agent-worthy.” The agents and criteria described by Bird (1993), Adler (1992), and Avouris et al. (1993) focus on the underlying organization of a system rather than the tasks performed for the user.

3. What is Anthropomorphism?

The Collins Concise English Dictionary shows that anthropomorphism did not originate with computer interfaces:

anthropomorphic adj. 1. of or relating to anthropomorphism. 2. resembling the human form. anthropomorphism n. the attribution of human form or behavior to a deity, animal, etc.

Anthropomorphism is the projection of human characteristics and traits onto non-human or inanimate objects, e.g. our pets and cars. We do this naturally in our daily lives referring, for example, to cars, ships, and aeroplanes as female.

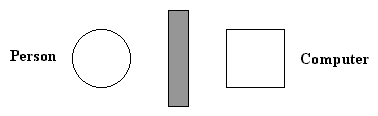

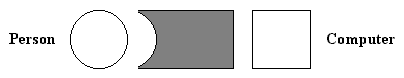

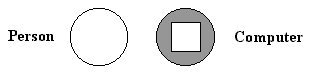

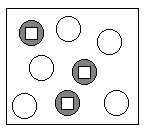

Anthropomorphic computer interfaces are certainly not new—at least in science fiction (Laurel 1990). The fundamental reason for using anthropomorphism is to produce an emotional response which forms a relationship between the user and the computer. Different degrees of anthropomorphism can be used, each with differing effects. Three degrees of anthropomorphism are shown below. Anthropomorphism may be as simple as (a) which is often found in educational software, or more complex like (c) which suggests character and personality like the agents used in the Guides system (see section 4.2).

Hello, I am the

computer…

The more life-like the representation of a human face used, the more the user attributes human intelligence to the computer (Oren et al. 1990). Bates (1994) describes the role of emotion in believable agents linking it with the notion of believable character in the Arts. This is not necessarily an honest or reliable character, but one that provides the illusion of life which permits the audience’s suspension of disbelief. Suspension of disbelief is the essence of anthropomorphic interfaces.

4. Three Examples of Anthropomorphism in Agents

This section discusses anthropomorphism in three agent-based systems: Object Lens, Guides, and Julia. These examples were chosen to highlight the varying degrees of anthropomorphism ranging from none at all (Object Lens) to fully anthropomorphic (Julia).

4.1 Object Lens

Object Lens is an intelligent information sharing system enhancing electronic mail by alleviating some of the problems of traditional email such as floods of unwanted junk and users being unaware of information in other parts of the organization that might be useful (Lai et al. 1988). Active rules for processing information are represented in semi-autonomous agents. Users create rule-based agents that process information automatically providing a natural partitioning of the tasks performed by the system. The user always has control over how much information is processed automatically. Object Lens is not anthropomorphic and does not need to be.

4.2 Guides

Apple’s Guides system is an educational hyper-media database covering American history from 1800 to 1850 (Oren et al. 1990). The aim of Guides was to reduce the cognitive load on users created by navigating the hyperspace while trying to learn. The guides are a simple form of agents that assume the role of storytellers as a metaphor.

The guides are prototypical characters from the period including an Indian chief, a settler woman, and a frontiersman. Each guide has a life story which gives them a point of view enabling them to present information to the user and explain why it is relevant. The guides were never explicitly developed as characters but Oren et al. found that users assumed or wanted characterization behind them. The guides are represented by an icon of the guide’s head, and users appeared to ascribe emotions to the guides and their relationship with them. This reflects the power of a human face to suggest personality and reinforces the naturalness of anthropomorphism (see section 3).

4.3 Julia

The most anthropomorphic agent is Julia (Foner 1993). Julia is a TinyMUD robot whose job is to pass as a human player in a MUD world . A MUD (Multi User Domain) is a textual multi-player game in which players invent characters which inhabit a fantasy world. In these worlds, the boundaries between what is human and what is a ‘bot (the MUD vernacular for software robot) blurs and such distinctions are not usually made. This means that to anyone who does not know that Julia is a ‘bot, she appears to be just another player. Indeed, many of Julia’s skills are to make her appear human to other players.

Her responses have the human characteristic of randomness allowing her to answer in varying levels of detail. This is an example of what Shneiderman calls “unpredictable” (see section 6). In this case it makes the illusion of Julia more complete and strengthens the mental model other players have of her. Julia has a discourse model which, while limited, helps when communicating with humans. Conversational partners expect each other to remember the objects and events recently referred to. Without this ability, conversations would be become strained and difficult. Julia is able to remember the last few interactions.

Julia is able to pass the Turing test and has been entered in the Leobner Turing Test competition. She must be convincing because it takes some time for most players to work it out. Foner gives the example of a player called Barry who, not knowing that Julia is a ‘bot, continues to make sexual advances to her even after being continually rebuffed. Julia’s attempts to look human enhance her utility even to those that know she is a ‘bot but they can also decrease it. For example, she often reverts to talking about ice hockey after a series of interactions which she fails to parse. In such a case, one player thought she was just a boring human.

5. The Case For Anthropomorphism

Laurel (1990) states that “anthropomorphising interface agents is appropriate for both psychological and functional reasons. Psychologically, we are quite adept at relating to and communicating with other people.” People have a tendency to anthropomorphise, to see human attributes in an action appearing in the least bit intelligent (Norman 1994). However, anthropomorphism is not the same thing as relating to other people; it is “the application of a metaphor with all it concomitant selectivity” (Laurel 1990). Anthropomorphism is not creating an artificial personality and “when we anthropomorphise a machine or an animal we do not impute human personality in all its subtle complexity; we paint with broad strokes, thinking only of those traits that are useful to us in the particular context” (Laurel 1990).

The practical requirement of producing the hundreds of thousands of drawings required to produce realistic cartoons, forced the Disney animators to use extremely simple, non-realistic imagery, and to abstract out the crucial elements (Bates 1994). It is this abstraction that is the basis of a mental model (Norman 1986). Traditionally, software functionality has been far more important than usability. The interface, if it was acknowledged at all, was a wall to climb—a barrier to even the simplest of tasks:

Metaphors provide a correspondence or analogy with objects in the real world the user is familiar with, such as the ubiquitous desktop. Such analogies enable the user to produce a mental model of a system. This improves the interaction by enabling them to predict system behaviour:

Anthropomorphism allows people to use their existing abilities to communicate and interact with people producing a more natural interaction:

Metaphors have their problems and are rife the Macintosh desktop for example. They also have their opponents such as (Nardi & Zarmer 1993).

Carbonell (1980) produced a comprehensive simulation model of human personality traits for a story understanding system. Character development is an important part of such a system. The reader of a story identifies with characters based on their attributes, e.g. heroism, compassion, intelligence, etc. Knowledge of the characters and their personality helps to interpret their actions and induce their goals (Carbonell 1980). Laurel (1986) states that “an interface is by nature a form of artistic imitation: a mimesis.” Although artistic approaches to design have, in the past, been considered “fluff,” she has developed a theory of interaction which compares computers and theatre (Laurel 1991). Laurel uses the 2000 year old Aristotelian theory of drama as a basis for which we can producing effective user interfaces. Her justification for modelling user interfaces on dramatic characters is that they are a familiar way of structuring thought and behaviour. Further, a body of theory and methodology is already available for creating them (Laurel 1989). Laurel calls this theory computers as theatre. Alan Kay, however, predates Laurel in comparing computers and theatre: “Context is the key, of course. The user illusion is theatre, the ultimate mirror. It is the audience (the user) that is intelligent and can be directed into a particular context. Giving the audience the appropriate cues is the essence of user-interface design” (Kay 1984).

In her theory, Laurel compares users of interactive software to the audience of a play: “users, the argument goes are like audience members who are able to have a greater influence on the unfolding action than simply the fine-tuning provided by conventional audience response.”

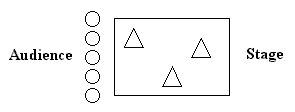

To become more interactive, the audience must join the actors on the stage. Laurel (1991) compares this to the avant-guard interactive plays of the 1960s which often degenerated into a free-for-all:

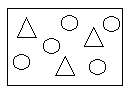

This is an important step in considering the future of agents in Virtual Reality (VR). Changing the actors (the triangles in the diagram above) to anthropomorphic agents and the stage for a computer environment, we arrive at the situation depicted below; people and artificial characters interacting in VR.

The MIT ALIVE System is such an environment (Maes et al., 1994). Using a “magic mirror,” in which a video image of a user is combined with objects and interface agents and displayed on a life-size screen. “Virtual worlds including autonomous agents can provide more complex and very different experiences than traditional virtual reality systems” (Maes at al 1994). The ‘personalities’ of artificial characters in cyberspace were the focus of Project OZ at Carnegie Mellon University (Rheingold 1992).

6. The Case Against Anthropomorphism

The most outspoken opponent of anthropomorphism in user interfaces is Dr Ben Shneiderman at the University of Maryland. While conceding that “… most people are attracted to the idea that a powerful functionary is continuously carrying out their tasks and watching out for their needs” (Shneiderman 1992) he describes them as “fantasies” and states that: “many users have a strong desire to be in control and to have a sense of mastery over the system, so that they can derive feelings of accomplishment.” Norman (1994) concurs with Shneiderman on this point:

“An important psychological aspect of people’s comfort with their activities—all of their activities, from social relations, to jobs, to their interaction with technology—is the feeling of control they have over these activities and their personal lives.”

Shneiderman (1992) indicates that anthropomorphism must lead to unpredictability by saying that “users usually seek predictable systems and shy away from complex unpredictable behaviour.” Unpredictability would certainly be a result of some of the characteristics of an agent. Laurel (1990) suggests offering the user a number of agents each with different characteristics from which to choose—like a job interview or theatrical audition. She also suggests providing an “identa-kit” enabling users to configure their agents from a set of basic characteristics and abilities.

Shneiderman (1993a) gives three objections to the user of anthropomorphism in user interfaces. Firstly, “the words and phrases used when talking about computers can make important differences in people’s perceptions, emotional reactions, and motivation to learn. Attributing intelligence, independent activity, free will, or knowledge to computers can mislead the reader or listener.” This is a valid point but human agents such as estate agents who are people with intelligence, independent activity, and free will, operate within the boundaries of their job and fulfil our expectations of them. Again, Shneiderman makes the valid point that “bank terminals that ask ‘How may I help you?’ suggest more flexibility than they deliver. Ultimately the deception becomes apparent, and the user may feel poorly treated.” This is simply an example of bad design with an unwarranted use of anthropomorphism and, as Laurel (1990) notes, “agents, like anything else, can be well or poorly designed.”

Secondly, in the context of children interacting with educational software: “the dual image of computer as executor of instructions and anthropomorphized machine may lead children to believe they are automatons themselves. This undercuts their responsibility for mistakes and for poor treatment of friends, teachers, or parents.” Laurel (1990) makes the same point which she calls an ethical argument against agents: “If an agent looks and acts a lot like a real person, and if I can get away with treating it badly and bossing it around without paying a price for my bad behavior, then I will be encouraged to treat other ‘real’ agents (like secretaries and realtors, for instance) just as badly.” Although Laurel (1990) provides many arguments against agents, only this one is about anthropomorphism.

Thirdly, again in the context of children using educational software, “an anthropomorphic machine may be attractive to some children but anxiety producing or confusing for others.” Although Shneiderman admits that his arguments are “largely subjective” and express his personal view he does cite several examples of empirical data that support them (Shneiderman 1993a). In an experiment of 26 college students, the anthropomorphic design:

“HI THERE, JOHN! IT’S NICE TO MEET YOU. I SEE YOU ARE READY NOW.”

was considered less honest than the mechanistic design:

“PRESS THE SPACE BAR TO BEGIN THE SESSION.”

Subjects took longer with the anthropomorphic design—possibly contributing to the improved scores on a quiz—but they felt less responsible for their performances. In a study of 36 junior high school students (conducted by Shneiderman) the style of the interaction was varied. Students worked with a CAI program in one of three forms: I, You, and Neutral.

| I: | "HI! I AM THE COMPUTER. I AM GOING TO ASK YOU SOME QUESTIONS." |

| You: | "YOU WILL BE ANSWERING SOME QUESTIONS. YOU SHOULD…" |

| Neutral: | "THIS IS A MULTIPLE CHOICE EXERCISE." |

“Before and after each session at the computer, subjects were asked to describe whether using a computer was easy or hard. Most subjects thought using a computer was hard and did not change their opinion, but of the seven who did change their minds, the five who moved toward hard-to-use were a in the I or Neutral groups. Both of the subjects that moved toward easy-to-use were in the You group. Performance measures on the tasks were not significantly different, but anecdotal evidence and the positive shift for You group members warrant further study” (Shneiderman 1993a).

Kay (1984) feels that agents are “inescapably anthropomorphic” but he does concede the limitations: “Agents are not human and will not be competent for some time. They violate many of the principles of user interface design; importantly that of maintaining the user illusion. If the projected illusion is that of intelligence and the reality falls far short, users will be disappointed” (Kay 1984). Norman (1994) points out perhaps the main disadvantage of using anthropomorphism:

“As soon as we put a human face into the model, perhaps with reasonably appropriate dynamic facial expressions, carefully tuned speech characteristics and human-like language interactions, we build on natural expectations for human-like intelligence, understanding, and actions.”

We want the metaphor of anthropomorphism to improve the interaction but we do not want the user to consider the computer to be intelligent (until such time that it really is). To meet users expectations, agents need more common sense than any present day system has (Minsky & Riecken 1994).

Industrial robots have long been compared to humans. No machinery has ever been so extensively personified; even the parts of a robot are named after human anatomy e.g., arm and wrist. People use anthropomorphism as a metaphor in order to make the technology understandable. However, the comparison of robots to humans has often made the technology fearful to would be users. McDaniel & Gong (1982) suspect that much of the resistance is based on misinformation about the industrial robot’s physical description and functions. They contend that inappropriate comparisons of robots to human workers have been made and that this anthropomorphism has interfered with the acceptance of robots.

As with the blurring of the boundaries between human players and software robots (‘bots) in a MUD (see section 4.3) so the boundaries between humans and VR ‘bots need not even be made. Consciousness would be the final characteristic a VR ‘bot would need to be indistinguishable from a human. They would not even need to know they were ‘bots. This is illustrated by the following extract from the science fiction film Blade Runner. Deckard and Tyrell are discussing Rachel the replicant who has just failed Deckard’s empathy test. The empathy test is designed to distinguish between humans and robots (the replicants). Rachel does not know she is a replicant which is why it takes Deckard so long to find out.

| Deckard: | She's a Replicant, isn't she? |

| Tyrell: | I'm impressed. How many questions does it usually take to spot one? |

| Deckard: | I don't get it, Tyrell. |

| Tyrell: | How many questions? |

| Deckard: | Twenty, thirty—cross-referenced. |

| Tyrell: | It took more than a hundred for Rachel, didn't it? |

| Deckard: | She doesn't know? |

| Tyrell: | She's beginning to suspect I think. |

| Deckard: | Suspect?! How can it not know what it is? |

7. Implications for HCI

One characteristic of human personality is lying or giving false information to someone for a particular reason. If an anthropomorphic agent were instructed to lie, how successful would it be in its deception? Could an anthropomorphic interface make people believe information that was not true? The answer to this question has important consequences. If anthropomorphism is more effective in making people believe information, even if it is not true, then it could be used with dubious motives such as advertising or propaganda. One study that investigated whether the source of information (person or computer) makes a difference to whether people believe it suggests that anthropomorphism may not be effective as a method of persuasion.

Anthropomorphism is undoubtedly important to HCI and agents—especially agents using multi-media. The latest version of Apple’s Guides system uses colour video and sound to present the guides extremely effectively using video of their ‘talking heads.’

With current techniques and future developments in video and sound editing, multi-media presentations can easily be developed. It will not be long before stock footage and sound can be spliced together seamlessly and automatically to a given specification. This has important implications for the presentation of false information especially with the current trend in television of docu-dramas, a combination of fact and fiction in a documentary or news reporting style.

A system, not unlike Guides, could be envisaged that, as well as presenting multi-media information to users, it could create it using a specification drawn up by a third party. Such a third party could be a commercial organization simply wanting its product placed in existing footage for advertising . Similarly, it could be used by a political organization to distort factual events to further their own ends. The Guides database would be a perfect application in which to do this. It would be particularly effective since most of the users would be susceptible school children.

People are known to have very different reactions and emotions towards material they believe to be factual events and those they believe to be fiction (Secord & Backman 1969). Director of the ultra-violent 1992 film Reservoir Dogs , Quentin Tarantino, acknowledges this:

“I think it [violence] is just one of the many things you can do in movies. But ask me now how I feel morally about violence in real life? I think it’s one of the worst aspects of America. But in movies, it’s fun. In movies, it’s one of the coolest things for me to watch. I like it” (McLeod 1994).

It would be far too simplistic to think that presenting false information using multi-media and getting people to believe it may be as simple as just stating that it is real. The style in which the video/film was made, however, e.g. drama, documentary, or news reporting, would be sure to have an effect. This style is the language of television and cinema which can communicate the same information to an audience in different ways. Finding the most effective style to present multi-media information to make people believe it is an important area of research. It would certainly draw upon the established body of film-making and theatrical knowledge including Laurel’s work on computers as theatre.

The results of such research may show that it takes surprisingly little to fool people. The classic Turing test of intelligence is such an example. If a computer can convince a person that it is intelligent it does not make the computer intelligent—just able to fool the person into thinking that it is intelligent.

8. The Future of Anthropomorphic Agents

Marvin Minsky muses on the old paradox of having a very smart slave (Minsky & Riecken 1994):

“If you keep the slave from learning too much, you are limiting its usefulness. But if you help it to become smarter than you are, then you may not be able to trust it not to make better plans for itself than it does for you.”

Anthropomorphic agents may develop to become so ‘real’ that they will loose their usefulness. However, as Minsky muses, if you limit the agent you limit its usefulness. If agents become so life-like and the illusion of life becomes so strong, then people will relate to their anthropomorphic agent as if it were a real person. One of Foner’s (1993) criteria, risk and trust, will increasingly dominate to become a handicap. Rather than exploiting the speed, accuracy, and reliability of the non-anthropomorphic computer, users will expect their computer to be slow, inaccurate, and unreliable because their agent’s character suggests (even insists) so well that it is human.

References

- Adler, Mark, Edmund Durfee, Michael Huhns, William Punch, and Evangelos Simoudis. AAAI Workshop on Co-operation Among Heterogeneous Intelligent Agents. AI Magazine, Summer 1992: 39-42.

- Avouris, Nicholas M., Marc H. Van Liedekerke, Georgious P. Lekkas, and Lynne E. Hall. User interface design for co-operating agents in industrial process supervision and control applications. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies (38) 1993: 873-890.

- Bates, Joseph. The Role of Emotion in Believable Agents. In Communications of the ACM, Volume 37, Number 7, July 1994: 122-125.

- Beale, Russell, and Andrew Wood. Agent-Based Interaction. In People and Computers IX: Proceedings of HCI ‘94. Cambridge University Press. August 1994: 239-245.

- Bird, Shawn A. Toward a taxonomy of multi-agent systems. International Journal of Man- Machine Studies (39) 1993: 689-704.

- Carbonell, Jaime G. Towards a Process Model of Human Personality Traits. Artificial Intelligence (15) 1980: 49-74.

- Foner, Leonard N. What’s An Agent Anyway? A Sociological Case Study. MIT Media Laboratory, 1993.

- Kay, Alan. Computer Software. Scientific American, Volume 251, Number 3, September 1984: 41-47.

- Kay, Alan. User Interface: A Personal View. In The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, edited by Brenda Laurel. Addison Wesley, 1990.

- Lai, Kum-Yew, Thomas W. Malone, and Keh-Chiang Yu. Object Lens: A Spreadsheet for Co-operative Work. ACM Transactions on Office Information Systems, Volume 6, Number 4, October 1988: 332-353.

- Laurel, Brenda. Interface as Mimesis. In User Centred System Design: New Perspectives in Human-Computer Interaction, edited by Donald A. Norman and Stephen W. Draper. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1986.

- Laurel, Brenda. Interface Agents as Dramatic Characters., Presentation for Panel, Drama and Personality in Interface Design. Proceedings of CHI ‘89, ACM SIGCHI, May 1989: 105-108.

- Laurel, Brenda. Interface Agents: Metaphors with Character. In The Art of Human- Computer Interface Design, edited by Brenda Laurel. Addison Wesley, 1990.

- Laurel, Brenda. Computers as Theatre. Addison Wesley, 1991.

- Maes, Pattie, Trevor Darrell, Bruce Blumberg, Alex Pentland. The AliVE System: Fullbody Interaction with Autonomous Agents. IEEE Computer special issue on Virtual Environments. To be published in 1994.

- McDaniel, Ellen, and Gwendolyn Gong. The Language of Robotics: Use and Abuse of Personification. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, (4) 1982:178-181.

- McLeod, Pauline. Just who is Quentin Tarantino? Flicks, Volume 7, Number 8, August 1994:16-17.

- Minsky, Marvin, and Doug Riecken. A Conversation with Marvin Minsky About Agents. In Communications of the ACM, Volume 37, Number 7, July 1994: 22-29.

- Nardi, Bonnie A., and Craig L. Zarmer. Beyond Models and Metaphors: Visual Formalisms in User Interface Design. Journal of Visual Languages and Computing, (4) 1993: 5-33.

- Norman, Donald A. Cognitive Engineering. In User Centred System Design: New Perspectives in Human-Computer Interaction, edited by Donald A. Norman and Stephen W. Draper. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1986.

- Norman, Donald A. How Might People Interact With Agents. In Communications of the ACM, Volume 37, Number 7, July 1994: 68-71.

- Oren, Tim, Gitta Salomon, Kristee Kreitman, and Abbe Don. Guides: Characterising the Interface. In The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, edited by Brenda Laurel. Addison Wesley, 1990.

- Rheingold, Howard. Virtual Reality. Mandarin, 1992: 308-309.

- Secord, Paul F., and Carl W. Backman. Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

- Shneiderman, Ben. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction. Addison Wesley, 1992.

- Shneiderman, Ben. A non anthropomorphic style guide: overcoming the Humpty Dumpty Syndrome. In Sparks of Innovation in Human-Computer Interaction, edited by Ben Shneiderman, Ablex Publishing, 1993a.

- Shneiderman, Ben. Beyond Intelligent Machines: Just Do It! IEEE Software, January 1993b: 100-103.